This material is the result of academic research conducted by the author at the University of Silesia and the University of North Carolina as part of a research grant from the National Science Centre of the Republic of Poland (Grant No. 2022/45/N/HS5/00961). The study was supervised by Maria Coady, Professor of Equity in the Department of Education at the University of North Carolina, Professor Aleksandra Niewiarra, a linguistics expert at the University of Silesia, as well as leading legal scholars, Professor Anna Chorążewska and Dr. Artur Bilgorajski, who are also heads of my academic program.

Since the onset of the full-scale invasion (2022), approximately six million Ukrainians have fled their homeland, with the vast majority seeking refuge in the European Union’s countries. Despite the EU’s established legal framework for refugees, integrating into a new society remains a significant challenge for displaced persons, particularly due to linguistic barriers.

This article presents the findings of my legal research on the use of native (first) languages among refugees from Ukraine and the adaptation of them to new linguistic environments.

Also read: "Право на використання рідної мови в Європейському Союзі: які можливості мають українці?".

Context

First and foremost, it is essential to define the term "refugee." The perception of this term within Europe has evolved over time.

According to the 1951 Geneva Convention, a refugee is a person who has been forced to leave their country of previous residence due to a well-founded fear of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. Refugee status is granted following an individual case assessment.

Additionally, European Union law defines the term "subsidiary protection status" (as specified in Directive 2011/95/EU). This status applies to individuals who do not meet the criteria of a refugee under the Geneva Convention but cannot return to their country of origin due to a serious (i.e., real) risk to their safety.

The most relevant status for Ukrainians today is "a beneficiary of temporary protection", a special protection status granted by the European Commission to Ukrainian citizens in response to the ongoing armed conflict in Ukraine. Unlike refugee or subsidiary protection status, temporary protection is granted automatically, without the need for an individual application review, and remains in effect until the European Commission decides to terminate it. Currently, the majority of Ukrainians in the EU hold this status.

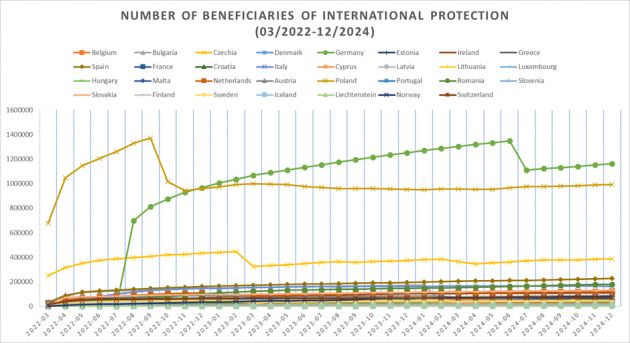

(Figure 1. Number of Beneficiaries of International ProtectionThe graph (Figure 1) illustrates migration trends from Ukraine to EU countries due to the ongoing war, covering the period from March 2022 to December 2024. Source of design: own. Data source: Eurostat)

As shown in Figure 1, Poland, Germany, and the Czech Republic are the top three host countries for Ukrainian refugees. This study focuses specifically on the situation of Ukrainian refugees in Poland, as this country has played a central role in the refugee response, which is reflected in the statistical data presented above.

Research overview

Objective

The primary goal of this research is to develop a standard for refugee protection in the context of language-related rights. The issue of linguistic adaptation among refugees is closely tied to the broader concept of language rights.

In general, language rights encompass all legal protections related to language use. A literature review has revealed that this category of rights is often associated with pedagogy and linguistics. Language rights are also discussed in the context of the rights of national and ethnic minorities as well as indigenous peoples (e.g., in the works of Tove Skutnabb-Kangas and Robert Phillipson).

It is also important to note that while the term “language rights” is not explicitly mentioned in international treaties, it is often interpreted as part of their provisions. For instance:

● The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) primarily considers language rights through the lens of freedom of expression, the right to respect for private and family life, and the right to a fair trial (particularly in cases involving the right to an interpreter during legal proceedings).

● Organizations such as the UN Human Rights Committee and the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe have issued recommendations regarding the protection of language rights, particularly in relation to migrants.

Language and Social Perception

Certain languages are widely accepted and valued within societies, while others may become sources of social tension or controversy. No international organization has the direct authority to enforce its policies within sovereign states, and even regional organizations like the European Union have only limited regulatory power over both refugee integration and language policy.

Given this, a key aspect of this research was understanding societal attitudes toward the linguistic challenges faced by refugees. In many ways, the situation of refugees depends on how they are perceived and received by the host society.

To analyze this, the study utilizes a theoretical model developed in the 1980s by American sociolinguist Richard Ruiz, who identified three primary orientations toward language within societies:

1. Language as a Right – This perspective views language as an inherent human right. It is based on the idea that every individual has the right to freely use their native language in all aspects of life, including education, public institutions, and legal proceedings. This approach emphasizes the protection of linguistic diversity and the rights of minority languages as a means of ensuring cultural richness and social justice.

2. Language as a Problem – From this viewpoint, multilingualism is seen as a challenge that complicates social integration and administrative efficiency. This approach often underlies language unification policies, which aim to simplify governance by promoting a single dominant language. It can also include assimilationist policies that pressure linguistic minorities to abandon their native languages in favor of the majority language.

3. Language as a Resource – This perspective considers language as an asset that can contribute to economic development, cultural enrichment, and social cohesion. Here, minority languages are recognized as valuable for preserving cultural diversity and fostering innovation.

Implications for Language Policy

These three conceptual orientations play a significant role in shaping language education policies and minority language rights. The prevailing societal perception of language directly influences how newcomers are integrated:

● A society that embraces the "language as a right" or "language as a resource" perspective is more likely to create conditions that support cultural and linguistic diversity.

● Conversely, societies that lean toward the "language as a problem" view are more likely to adopt policies focused on assimilation and linguistic homogenization.

Understanding these orientations is crucial for assessing how different countries approach refugee integration and the role that language policies play in shaping these processes.

Key Language Rights for Refugees

Based on the previously discussed theoretical concepts, four fundamental language-related rights can be identified as crucial for refugees at different stages of their integration into a host country:

1. The right to access information in one's native language when using public services.

2. The right to learn the language(s) of the host country to facilitate integration.

3. The right to study and use one’s native language as part of cultural and linguistic identity.

4. The right to use one’s language in legal proceedings, ensuring fair access to justice.

For refugees, the legal foundation for these rights is derived not only from the 1951 Refugee Convention and EU directives on international protection, but also from broader anti-discrimination frameworks. These include the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1965), and both the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966).

In addition, international institutions such as the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) have played a role in shaping the legal landscape of language rights.

Case Law on Language Rights and Discrimination

The ECtHR has addressed language rights in several landmark cases, primarily through the lens of freedom of expression, privacy rights, and the right to a fair trial.

● In cases related to freedom of expression, such as Mestan v. Bulgaria, Tatar and Fáber v. Hungary, Vajnai v. Hungary, and Mentzen v. Latvia, the Court ruled that while it cannot dictate national language policies, excessive restrictions—such as imposing fines or penalties that de facto limit free speech—constitute violations of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

● The ECtHR has also recognized non-verbal actions, such as displaying symbols, as part of freedom of expression. However, in cases such as Mentzen v. Latvia, the Court did not rule in favor of the applicant’s right to write their name in their native language, considering it instead as a matter of private and family life rather than linguistic freedom.

In the context of education, the Court’s landmark ruling in D.H. and Others v. the Czech Republic condemned the segregation of Roma children in Czech schools, finding that the entire school system failed to meet ECHR standards. As a result, the Czech government eliminated specialized schools that had systematically placed Roma children in programs for students with intellectual disabilities.

Since the D.H. ruling, the Court has further clarified the issue of language-based discrimination in education:

● In Sampani and Others v. Greece, the ECtHR condemned physical segregation in mixed schools.

● In Oršuš and Others v. Croatia, the Court ruled that language proficiency cannot serve as a basis for school segregation, as it violates Article 14 of the ECHR.

● In Horváth and Kiss v. Hungary, the ECtHR explicitly stated that "neutral" educational policies cannot result in indirect discrimination against linguistic minorities.

Challenges in the Implementation of Language Rights

Despite these international legal principles and ECtHR rulings, their practical application at the national level remains inconsistent. The ECtHR generally avoids direct interference in national language laws. For instance, in Igors Dmitrijevs v. Latvia, the Court declined to rule on the language of public administration services, refraining from assessing whether state agencies must provide services in languages other than the official national language.

Language Barriers in Refugee Integration

A common misconception in Ukraine is that English is universally spoken across Europe. However, this is far from reality. In countries like Poland, while many young people have a good command of English, public administration and legal services operate almost exclusively in Polish. According to the Constitution of the Republic of Poland (1997), the official language of public institutions is Polish. This presents significant challenges for refugees:

1. All official documents and legal evidence must be submitted in Polish. Those who cannot do so must hire a translator/interpreter at their own expense.

2. Public authorities are not required to respond in any language other than Polish. The only exception is in court proceedings, where international law mandates access to an interpreter.

Impact on Refugees and Their Integration

Ultimately, refugees—who should be protected from discrimination—face significant linguistic barriers that affect their ability to integrate into society.

Challenges for Ukrainian Children

Children are among the most vulnerable groups in any society, and Ukrainian refugee children face particularly difficult circumstances.

● Many have been forcibly displaced, leaving behind their homes, friends, and sometimes even family members.

● They must quickly adapt to a new educational system in an unfamiliar linguistic environment.

● In Poland, for example, education is conducted in Polish, meaning that refugee students must learn the language to keep up with their peers.

A major challenge is that students must pass the same exams as native speakers, including advanced Polish language exams. While some Ukrainian students perform well in mathematics and science, they struggle with language assessments, which can lead to failing grades.

● In several EU countries, failing a single subject—including language exams—can result in a student being required to repeat an academic year.

● This can have severe consequences, such as dropping out of school, being unable to obtain a diploma, and losing motivation to pursue higher education.

Policy Responses in Poland

Before the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, most EU countries, including Poland, did not have separate educational programs for refugee children. The issue of refugee integration into national school systems was simply not a high-priority policy concern.

However, following the 2022 refugee crisis, the Polish Ministry of Education and Science recommended enrolling Ukrainian students in preparatory classes within Polish schools. These special classes grouped students of different ages together, creating significant challenges for full curriculum implementation. As a result, these classes focused primarily on Polish language courses, rather than a comprehensive education.

Preparatory classes for foreign students existed in Poland before 2022, but they were not widely used before the mass arrival of Ukrainian refugees. This presented a major challenge for the Polish education system. Over time, adjustments were made to improve refugee education policies:

● The Polish language exam requirement in public schools for Ukrainian students was recently abolished.

● Starting in September 2024, a new position of “intercultural assistant” will be officially introduced in schools. These professionals are required to:

○ Communicate in the students’ native language.

○ Understand the cultural backgrounds of both refugees and the local community.

○ Facilitate cross-cultural dialogue in schools.

However, it is crucial to note that these policies are not designed to support the learning of Ukrainian as a native language. Instead, their primary goal is to help students quickly master Polish, the language of instruction.

Alternative Models: The Case of Sweden

A contrasting approach can be seen in Sweden, where language access is enshrined in law. According to Sweden’s 2009 Language Act, the state must ensure linguistic diversity and provide access to a person’s preferred language. In administrative services, the cost of translation is covered by the government, not by the individual.

Sweden’s approach significantly reduces instances of discrimination against refugees in schools. If a refugee child enrolls in a Swedish school, they have the right to receive instruction in their native language. Schools hire specialists who translate and duplicate lessons in the student’s language. This allows for a gradual transition to learning Swedish, easing both academic adaptation and social integration. As a result, students do not feel that their native language is an obstacle but rather a valued part of their identity.

Broader Implications

Language barriers are not only a challenge for children but also for adult refugees. Limited proficiency in the majority language can result in difficulties accessing public services, securing employment, and applying for residency or driver’s licenses. Historical examples, such as the 1950s Texas government reports on Spanish-speaking communities, suggest that without proper policies, refugees may face long-term disadvantages in education and economic opportunities. Without strategic solutions, Europe may face similar challenges in the years ahead.

Conclusions

Language support plays a critical role in the integration and adaptation of refugees, particularly children, who are among the most vulnerable to traumatic experiences. Without adequate linguistic assistance, there is a risk of forming isolated communities, which can lead to the emergence of social “ghettos.”

Therefore, education systems and social institutions must prioritize language rights and support, as these are key factors in effective integration and reducing the risks of social exclusion.

One possible solution to this complex issue is engaging representatives of national minorities in the refugee adaptation process and incorporating refugees into programs designed to support national minorities. A relevant example is the educational initiatives for the Ukrainian national minority in Poland, which are particularly significant for refugee children.

This issue is already the subject of ongoing academic research. Given the rapid sociocultural changes in Europe, new evaluation criteria for the linguistic situation of refugees are expected to be developed in the near future. These criteria will allow for a comparative analysis of EU policies on refugees and an assessment of their impact on integration.