On 28 September 2017, Ukraine’s new education law entered into force.[1] Beyond setting a framework for a large-scale school reform, the law regulates the language of education. In seeking to strengthening the prominence of the Ukrainian language, the law triggered a wave of criticism from neighbouring countries that have minority populations in Ukraine, namely Bulgaria,[2] Greece,[3] Hungary,[4] Moldova,[5]Romania[6] and Russia.

While introducing Ukrainian as the obligatory language of instruction in secondary schools, the law does not appear to include any manifest violations of European obligations. Instead, he significant backlash that has erupted against the law may be a result of a law-making process, which was not consultative, highlighting a serious weakness in Ukraine’s law-making process.

The particularly vocal campaign against the law launched by the Hungarian government law, which argued that the law does not meet the European human rights standards, may also be explained by the fact that Hungary’s nationalist government saw the law a chance to mobilise domestic opinion ahead of elections next year.

Positively, the Ukrainian government submitted the law to the Venice Commission of the Council of Europe, expressing its commitment to implement the Commission’s recommendations.

What Does the Law Say about Languages?

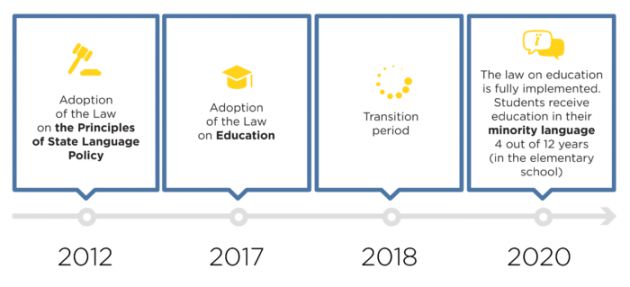

The controversy was triggered by Article 7 of the law, which states that instruction in secondary schools across Ukraine is to be conducted exclusively in Ukrainian. The provision changes the current situation, which is governed by the Law on the Principles of State Language Policy of 2012, that allows instruction to be provided in minority languages at schools in the regions where minorities represent more than ten per cent of the population – provided that the teaching of Ukrainian is ensured to the extent required for the socialisation of minority pupils.[7]

The new law foresees a three-year transition for the implementation of the law, with the gradual increase of subjects taught in Ukrainian for minorities.

Ukraine’s government has explained that Article 7 “clearly ensures the right of national minorities in Ukraine to maintain their collective identity through the medium of their mother tongue at primary and secondary levels of education.”[8] In this vein, the law guarantees the right of national minorities to study primary school (the first four years of school) in their minority language. Moreover, at the secondary level, the law ensures the right of national minorities to learn their minority languages as a separate subject. In addition, the law does not prohibit the possibility of establishing private education institutions that provide education in minorities languages.

Objectives of the Change?

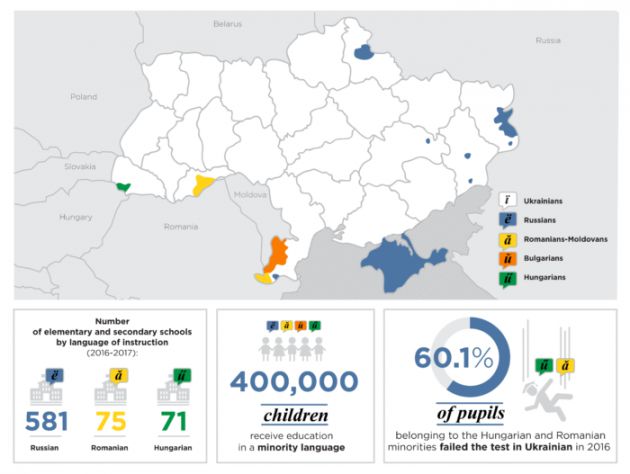

Ukrainian officials have stressed that the law aims to bring the education system closer to European standards and ensure equal opportunities for all. An increasing number of graduates from minority schools fail to pass the Ukrainian language test (60.1% of pupils belonging to the Hungarian and Romanian minorities failed the test in Ukrainian in 2016).[9] As such, the government claims that the law aims to improve the prospects of minorities in higher education and employment in the public sector. In these fields, proficiency in the state language is a requirement and, thus, the law is supposed to enhance the equality of opportunities for all members of Ukrainian society.

Although the government claims to be promoting equal opportunities for minorities, it appears that representatives of the minorities were not consulted during the drafting of the law. There are no references to such consultations in the explanatory notes to the law. The issue of consultation with minorities was also not raised at parliamentary hearings when the law was discussed. The harsh criticism by minorities further indicates that the process was not inclusive.

Although the government claims to be promoting equal opportunities for minorities, it appears that representatives of the minorities were not consulted during the drafting of the law. There are no references to such consultations in the explanatory notes to the law. The issue of consultation with minorities was also not raised at parliamentary hearings when the law was discussed. The harsh criticism by minorities further indicates that the process was not inclusive.

The International Reaction: Hungary Calls Brussels and Strasbourg for Help

The Russian State Duma and Federation Council adopted a resolution alleging that the law infringes the rights of Russian minority in Ukraine. Romania’s parliament adopted a resolution criticising the law, warning that it would hinder Ukraine’s integration with the EU. The most vocal and detailed criticism came from the Hungarian government, which claimed Ukraine had violated its commitment under the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement (in full force as of September 2017) to respect democratic principles and fundamental freedoms, including the rights of national minorities.[10] Hungary also accused Ukraine of not following Resolution 2145 (2017) “The Functioning of Democratic Institutions in Ukraine” of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), which calls upon the authorities to “preserve the current rights to use minority languages.” Hungary also included this issue in the Eastern Partnership Declaration that is to be issued at the Eastern Partnership summit in Brussels in November. Furthermore, the Hungarian government has stated that the new legislation is not in line with the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (“Framework Convention), or the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (“European Charter”).

What Does International Law say?

In light of the international political tension the law and its criticism have caused, Ukraine submitted the law for review to the Venice Commission of the Council of Europe and expressed its willingness to follow the Commission’s recommendations. It appears that under international law, language matters are ultimately a sovereign issue of the state and it is legitimate for a state to demand the official language as the language of education for all. However, the Council of Europe’s human rights treaties require states to ensure the development of regional and minority languages (Article 8 of the European Charter). In particular, states are called upon to provide “adequate opportunities for being taught in the minority language or for receiving instruction in this language” (Article 14 of the Framework Convention). At the same time, it is up to the state to determine what measures it will take to fulfil this requirement, considering the possible financial, administrative and technical difficulties.[11] These measures have to further correspond with the principle of non-discrimination and maintain an appropriate balance with measures undertaken to promote the official language of the state.

In several cases, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has commented on the right to receive education in a native language. The ECtHR has concluded that, although Article 2 of Protocol II to the ECHR does not directly speak of the right to education in a native language, this right would be meaningless if it is not accompanied by the right to be educated in a native language.[12] In two cases, the ECtHR obliged state parties to ensure secondary school education in minority languages. However, the situations where the Court did so differ significantly from Ukraine’s situation. Both cases were related to the failure of the authorities of two self-declared states, namely Northern Cyprus[13] and Transnistria,[14] to guarantee secondary education in the Greek and Moldovan/Romanian respectively.

The national legislation to protect minority languages varies across Europe. Most of the states that expressed their concerns about Ukraine’s new education law guarantee, at least in theory, education in minority languages at all levels. In Hungary, for instance, Article 5 of the Act on Public Education provides that “the language of kindergarten education, school education and teaching […] is Hungarian, or the language of a national or ethnic minority.”[15] Similar provisions can be found in Article 10 of the Education Code of the Republic Moldova,[16] Article 10 of the Education Law of Romania[17] and Article 14 of the Education Law of the Russian Federation.[18] The exception is the Bulgarian National Educational Act, which grants rather narrow rights for national minorities in the field of education. Article 8 of the Act reads as follows: “pupils whose mother tongue is not Bulgarian, besides the compulsory study of the Bulgarian language, shall have the right to study their own mother tongue outside the state school in the Republic of Bulgaria under the protection and control of the state”.[19]

In the absence of an international obligation to ensure comprehensive school education in minority languages, what recommendations should be expected from the Venice Commission? Provisional indications can be found in the PACE Resolution 2189 (2017) of 12 October 2017[20] that criticises Ukraine’s education law for 1) its “heavy reduction in the rights previously recognised to ‘national minorities’ concerning their own language of education”; 2) adopting the law without “real consultation with representatives of national minorities”; and 3) an insufficient transition period. The main question for the Commission will be whether the law’s objective of producing students who are fluent in the state language could be achieved in a way that would be less restrictive. For this, the Commission will also assess whether the law provides for a balance between the promotion of Ukrainian and guarantees for minority languages. Considering the sensitivity of the matter, the fact that there is no one standard for the protection of minorities languages and that the law is already in force, the recommendations are likely to be quite general.

Conclusion

For Ukrainian policy-and law-makers, the education law showcases once again the importance of transparency and inclusiveness in the legislative process. Since there is no one-size-fits-all solution for the matter and probably no violation of international obligations has been committed, the wide-spread critique might have been avoided if the Ukrainian government demonstrated that it consulted – and came to an agreement with – the respective national minorities about the path forward with the issue. One step towards dialogue was made on 19 October through the meeting of the Ukrainian Minister of Education and the Hungarian Minister of Human Resources. The Hungarian official expressed respect for the Ukrainian attempts to strengthen the study of Ukrainian language.[21]

[1] See the text of the Law on Education (in Ukrainian) <http://zakon3.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2145-19/print1486580363615849>

[2] “Bulgaria: New Law On Education in Ukraine Violates the Rights of Bulgarian Minorities, Weapon News, 28 September 2017. <http://weaponews.com/news/15532-bulgaria-new-law-on-education-in-ukraine-violates-the-rights-of-bulgar.html>

[3] “Romanian, Bulgarian, Greek, Hungarian Foreign Ministers Sign Joint Letter on Ukraine’s Education Law,” Publika, 15 September 2017. <http://en.publika.md/romanian-bulgarian-greek-hungarian-foreign-ministers-sign-joint-letter-on-ukraine-s-education-law_2640210.html>

[4] “Hungary Urges Ukraine to Change Education Law,” LB, 6 September 2017. <https://en.lb.ua/news/2017/09/06/4443_hungary_urges_ukraine_change.html>

[5] “Ukrainian Education Law Is Unfair towards Moldovans and Hungarians, – Dodon” 112, 11 September 2017. <http://112.international/politics/ukrainian-education-law-is-unfair-towards-moldovans-and-hungarians-dodon-20637.html>

[6] “Romania, Concerned over New Ukrainian Education Law,” Romania Insider, 8 September 2017. <https://www.romania-insider.com/romania-ukrainian-education-law-september-2017/>

[7] See Article 20 of the Law on the Principles of State Language Policy (in Ukrainian). <http://zakon2.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/5029-17>

[8] See the Statement on the Law of Ukraine on Education, as delivered by Ambassador Ihor Prokopchuk, Permanent Representative of Ukraine to the International Organizations in Vienna, to the 1157th meeting of the OSCE Permanent Council, 28 September 2017. <http://mfa.gov.ua/en/press-center/news/60121-statement-on-the-law-of-ukraine-on-education>

[9] See “The Law on Education and Zakarpattia: What do the national minorities think and how the Law will be implemented.” (in Ukrainian) <https://goloskarpat.info/society/59de4eaf58ac6/?utm_content=03141>

[10] See Title II, Art. 4 of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement. <https://kijev.mfa.gov.hu/eng/news/tiltakozas-az-uj-ukran-oktatasi-toerveny-ellen>

[11] See Article 14 of the Framework Convention <http://www.ecml.at/Portals/1/documents/CoE-documents/FCNM_ExplanReport_en.doc.pdf>

[12] Belgian linguistic case, Judgment of 23 July 1968, para. 3, p. 31. <https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-57525%22]}>

[13] Case Cyprus v. Turkey, Judgment of 10 May 2001, para. 278. <https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22dmdocnumber%22:[%22697331%22],%22itemid%22:[%22001-59454%22]}>

[14] Case Catan and Others v. Moldova and Russia, Judgment of 19 October 2012 <https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-114082%22]}> para. 143-144

[15] Government of Hungary, “Act No. LXXIX of 1993 on Public Education.” <http://www.nefmi.gov.hu/letolt/english/act_lxxxix_1993_091103.pdf>

[16] The Parliament of the Republic of Moldova, “Education Code of the Republic of Moldova No. 152 dated July 17, 2014.” <http://edu.gov.md/sites/default/files/education_code_final_version_0.pdf>

[17] Romania Ministry of Education, “Law of National Education.” <http://keszei.chem.elte.hu/bologna/romania_law_of_national_education.pdf>

[18] See the text of the Law on Education of the Russian Federation (in Russian) <http://zakon-ob-obrazovanii.ru/14.html>

[19] Republic of Bulgaria, “National Education Act.” <http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/UNTC/UNPAN016454.pdf>

[20] See the PACE Resolution 2189 (2017) http://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/Xref-XML2HTML-EN.asp?fileid=24218&lang=en

[21] See the information about the meeting of the Hungarian and Ukrainian ministers (in Ukrainian <https://espreso.tv/news/2017/10/19/ugorschyna_pogodylasya_z_ukrayinskym_zakonom_pro_osvitu_ale_potribni_peregovory> and <http://transkarpatia.net/transcarpathia/politic/88802-ukrayina-kaptulyuvala-pered-ugorschinoyu.html>